Continuous Delivery Sounds Great but Will It Work Here

Over the last 7 years I have heard lots of reasons on why people can't do Continuous Delivery. This is my summary of these reasons and why they are wrong.

What is Continuous Delivery?

Fundamentally it is about making releases boring.

The ability to get changes – features, configuration changes, bug fixes, experiments – into production or into the hands of users safely and quickly in a sustainable way.

The reason Dave and I wrote the book was because we had to do releases during weekends and we didn't want to do that any more.

What went into the book were all the techniques we've found for fixing that problem.

2004, 2005 and 2006: we were able to fix that not by doing smart things with different tools

- Puppet, Chef, Terraform and the Cloud didn't exist.

- we did it basically with Bash, CVS, and talking to people

Talking to people was the most important thing.

most of the problems were:

- poor communication between development, testing and operations

- people using different tools

- people not trusting each other

Most of the solutions:

- getting people together and collaborating

- doing process improvement work

Ultimately we succeeded -> we never had to do releases again, we did it during normal business hours

It was a process that was not exciting and using not exciting technology.

Continuous Delivery Test: Can you release by the press of a button sitting in a bar drinking a Mojito? You can do that? Yes! You passed.

Yeah that talk probably needs revising for the COVID era, "…sitting in your bedroom drinking a coffee and quietly muttering to yourself"

– Jez Humble (@jezhumble), Dec 5, 2021

Ingredients of Continuous Delivery

Configuration Management

A new person starting in your team should be able to check out from version control the entire system, be able to run a single command to build the software, run the automated tests, and run a single command to deploy to any environment.

If it takes you days or weeks to get people up and running, hat is a configuration management problem.

You should be able to add capacity to your production system in a fully automated way by plugging in new servers, boots these servers, installs the right version of the OS, right version of the middleware, configures everything and configures the routers.

Continuous Integration

Continuous Integration Test:

- Does everyone in the team push to a shared trunk or main at least once a day? If you work on a long-running feature branch that does not get merged into trunk at least once a day, put your hands down.

- Does every commit to the shared trunk triggers an automated build and automated execution of all of the tests?

- If the build fails does it get fixed within ten minutes?

If you answer yes to all three questions -> Continuous Integration!!

Continuous Integration is not running Jenkins against your feature branches.

Continuous Integration is a practice.

My favourite paper on Continuous Integration is "Continuous Integration on a dollar a day" by James Shore.

- run the build and tests on local machine

- get the rubber chicken

- pull from the shared trunk on the local machine

- run the build and tests again: you do it twice so you know if it fails it was your changes or the merge

- push into the shared trunk

- run the build and tests again on the build machine

- then you are done

- the rubber chicken is available for the next person

If the build fails you have two options:

- go back to your machine: you have a few minutes to fix it

-

if you can't fix it in a few minutes, you revert

as simple as that

The most selfish thing you can do as a developer is leave broken code on trunk.

That's the practice of Continuous Integration.

The key thing is in the name: Continuous Integration!!! everyone is pushing to a shared trunk once a day at least, working in small batches

Testing

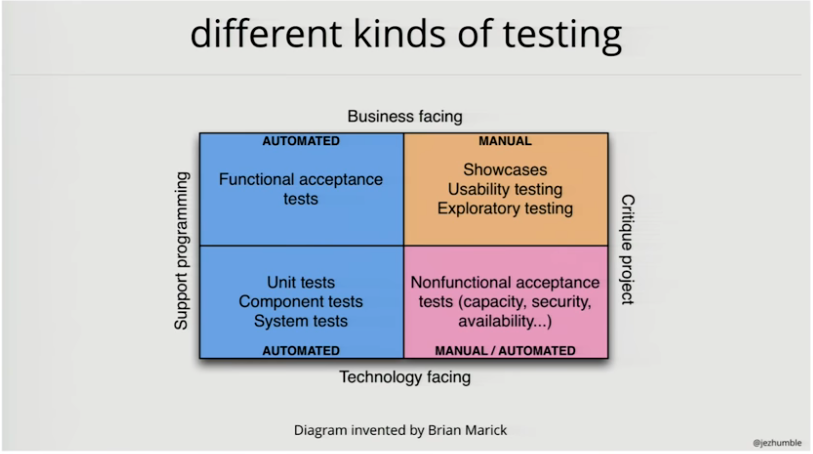

There are all kinds of tests that we are doing as a team.

At the bottom: unit tests, component tests, system tests - tests developers write to validate the system behaves according to expectations.

-> the only way to create a maintainable suite of unit tests: through TDD, it forces you to design the system in a testable way

If you try to retrofit unit tests on a system that wasn't designed with TDD it becomes painful and expensive. The system is hard to test because you didn't write the tests first.

On the top right: the things you can't automate - showcases, usability testing, exploratory testing -> manual activities

On the top left: automated functional acceptance tests, i.e. end-to-end tests who tests business processes all the way through

The stuff on the left = regression suite, the reason it is automated? there is no other way out to speed up the release process, doing this manually takes just too long and it is too error-prone

On the bottom right: some are manual, some are automated - capacity testing, security testing -> the crucial thing is you want to do this all the time from the beginning of your product, it tests the architecture of your product.

Architecture: the things that are hard to change (Martin Fowler)

if you find out at the end the performance is not right, you are in big trouble

There have been a lot of controversy around automated tests in the Testing Community. James Bach suggested to speak about automated checks instead. I think it is a loosing game trying to redefine existing terms.

However, the underlying issue is a real one, I want to be very clear about this:

Continuous Delivery is not about getting rid of testers. Testers are a vital and central role in the software delivery process. It is not to do manual regression testing. The job of Testers is to help the team understand the quality of the system so they can make decisions about it. To do exploratory testing, to create feedback loops, from exploratory testing to acceptance testing to unit tests. To help build and maintain the suites of automated tests with developers. It does not require Testers need to know about programming at all. I have seen very successful teams where testers pair with programmers and create automated tests and maintain them together. It is the best way to create maintainable tests.

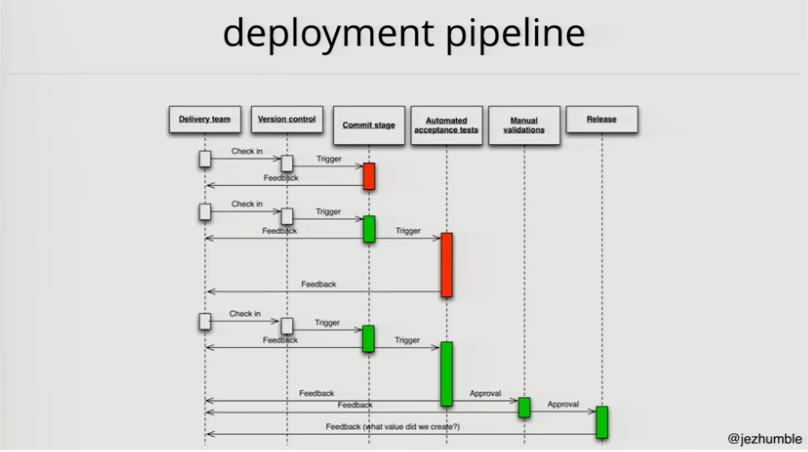

Deployment Pipeline

Once you have the tests, you create a deployment pipeline.

You should be able to recreate an environment (except the data, this is in the database) from version control on-demand in a fully automated way.

Any time you apply a change to the system:

- triggers the unit tests, they should run in a few minutes

- if they break, no-one checks in unless they are fixing it

- once you fix the unit tests that triggers longer running automated acceptance tests, you run them in parallel, should complete in the order of tens of minutes

- if they break, someone works on fixing it, you don't block commits however

- once we have these running, we can go more downstream to more long running tests:

- performance tests

- exploratory testing

- usability testing

- those tests take much more time and resources, they are expensive, so we don't run them as long as we know the build is reasonably good, i.e. pass all automated tests

- then we should be able to provision staging by a push of the button

You can trace every change!

- through the builds

- the environments and the tests it has been in

- all the way to production

- and have high confidence a build went through this process and is releasable

It won't work here because …

Main reasons I heard why Continuous Delivery is not possible:

- We're regulated

- We're not building websites

- Too much legacy

- My personal unfavourite (and I have heard this in real life): Our people are too stupid

These aren't the actual reasons.

The actual reasons are:

- Our culture sucks

- Our architecture sucks

Part the first: "we're regulated"

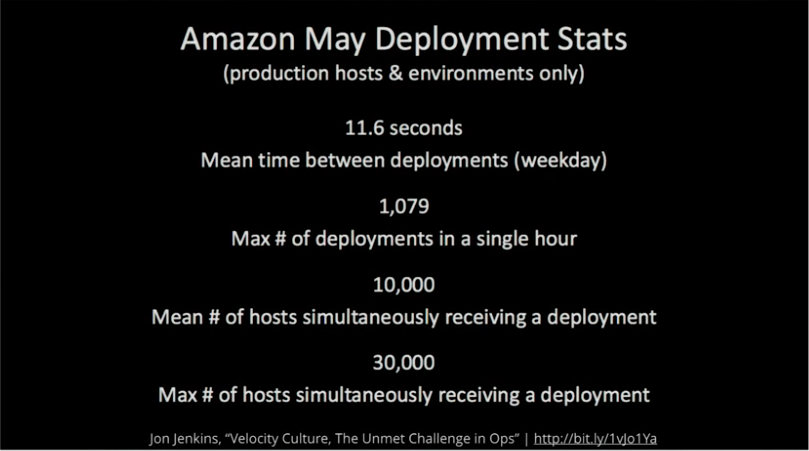

Example: Amazon

I like to show to people that say "we're regulated" this slide from Jon Jenkins, Velocity Culture, The Unmet Challenge in Ops at the 2011 Velocity Conference

Amazon makes changes to production every 11.6 seconds.

They are an order of magnitude faster now, 6 years later. They keep getting faster even when they keep getting bigger, which is one of the signs they got an architecture that enables Continuous Delivery.

Amazon is a publicly traded company -> have to follow Sarbanes-Oxley.

Amazon processes credit-card transactions -> have to follow PCI-DSS.

Amazon is heavily regulated!! This was extremely painful and expensive for Amazon to do this. They spend 4 years re-architecting their production environment to allow them to do this. This is non-trivial.

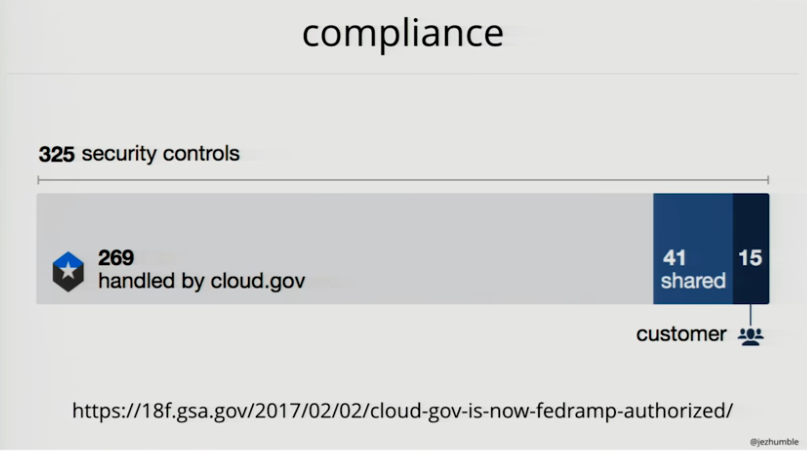

Example: cloud.gov

When you are building services in the US government you have to follow a shear amount of regulation. To launch a moderate impact system in the US federal government you have to implement and document and test and document the test of 325 information security controls. That typically takes 6 to 12 months after dev-complete before you can launch the service.

Most of these controls are operational controls, things like having backup power and fire extinguishers in the datacenter, all the way through to controls on the change management. Some of these controls are implemented by Amazon. cloud.gov build a platform as a service (PaaS) on top of AWS where they implemented a lot more of the controls. It took us a year to build that and then another 9 months to go through the certification process.

In the end: from the 325 security controls, 269 were handled by cloud.gov. Meaning if you were deploying an application on top of cloud.gov you only had to worry about 15 to 56 of those controls. It heavily reduced the time it takes to go from dev-complete to live in the heavily regulated organisations of the US federal government. This is something they can do in days or weeks.

All changes to cloud.gov happen through Continuous Delivery.

The reason I did that is so that I can say:

We are doing this in the heavily regulated US federal government. What is your excuse?

This is the most heavily regulated environment I ever worked in. People are so careful because frankly they don't want to end on the front of the Washington Post.

A lot of the reasons people say we can't do this in a regulated environment is:

-> Change Management

Does change management work?

all production changes must be approved by an external body (e.g. change approval board, manager, etc.) before deployment or implementation

vs no change approval process or peer review to manage changes

– source: State of DevOps Report 2014, Accelerate

What we found is -> approval by an external body does not work!

change advisory boards substantially

- reduces throughput, it makes it much slower to get changes out

- completely uncorrelated with time to restore service and the failure rate of your changes

=> having an external body approving changes does not work, it makes just things slower

having a peer review process is more effective and having no change approval process is actually more effective

=> our research shows that that reason "Change Management" why you cannot do CD in a regulated environment actually doesn't work at all

What does work? -> having a Deployment Pipeline

This is much better than a piece of paper that says if someone may or may not have done something and all the boxes have been ticked. We all know the reason why you have ticked all the boxes is that if something goes wrong you can say: "Look I have ticked all the boxes, it is not my fault".

Most change management is Change Management Theatre. It is not about making things better, it is about covering your ass when things go wrong. There is a better way to do it. Continuous Delivery is actually more important when you have a regulated environment.

Part the second: "we're not building websites"

My favourite case study of Continuous Delivery is actually from a firmware

Example: HP Laserjet Firmware

The reason why I like it because people don't tend to update their firmware 10 times a day.

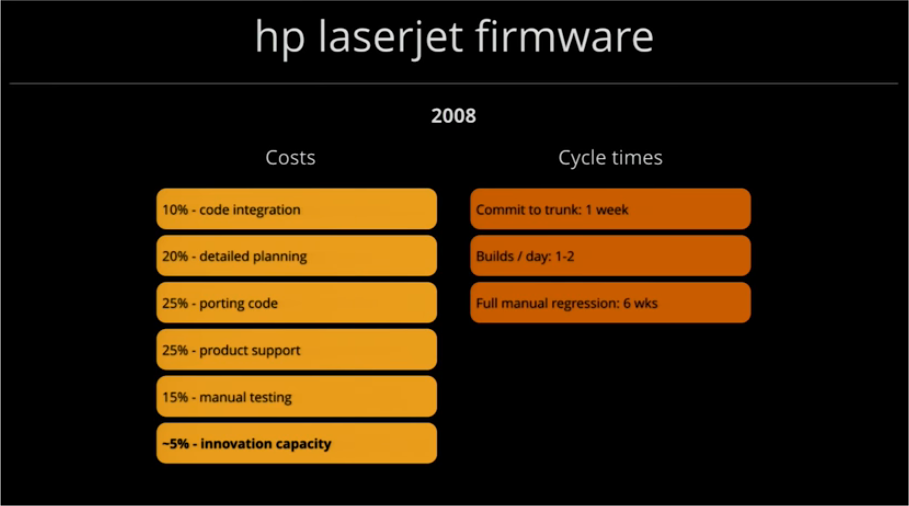

2008: problem: The firmware team is on the critical path for all new ranges of printers and scanners. That was true for years. They tried so many things: hiring people, firing people, insourcing, outsourcing, all the usual things. In the end they were so desperate they went to the engineering management to get help.

The engineering management did something interesting: activity accounting (vs cost accounting where you end up getting rid of what are the highest costs, yeah, right, the people, we all know where that ends). They looked at which activities the budget was being spend on.

- 10% code integration

- 20% detailed planning as the engineers fought with the product people to explain why they are so slow with excruciating detail: estimating

- 25% porting code: every time they release a new range of devices they take a branch in version control, any time they have a bug or a feature that have to work on multiple different products they have to pull that code across the branches

- 25% product support: it tells us it is a quality problem

- 15% manual testing

- -5% innovation capacity: when you subtract all the above from 100%, what you are left with is 5% to actually build features

Here you are in an organisation where you say: "we'd love to do some test automation and refactoring" but the managers says: "we'd love to support with that but we can't because we haven't got time, get on building the features".

The flaw in the argument with the above information becomes very obvious:

The reason you are so slow is because your time and budget is always consumed by non-value adding work. The only way to get out of that mess, is to actually address that.

Some cycle time metrics:

- commit to trunk: 1 week

- builds/day coming out of trunk: 1-2

- full manual regression testing: 6 weeks

They did something crazy. I wouldn't recommend it, but it worked for them.

They re-architected the entire system from scratch:

- reduce hardware variation: they agreed with the hardware people there would be only one hardware for all the different ranges of devices

-

create a single package: because only one hardware platform -> they can deliver one single package that run on all the different devices

there was still variation between devices: handled by configuration options or feature toggles

- implement continuous integration: because of one single package -> allowed them to implement continuous integration

- implement comprehensive test automation: to make that work, they had to create an awful lot of automated tests

- create a simulator for the target hardware platform: in order to make those automated tests work on developer workstations

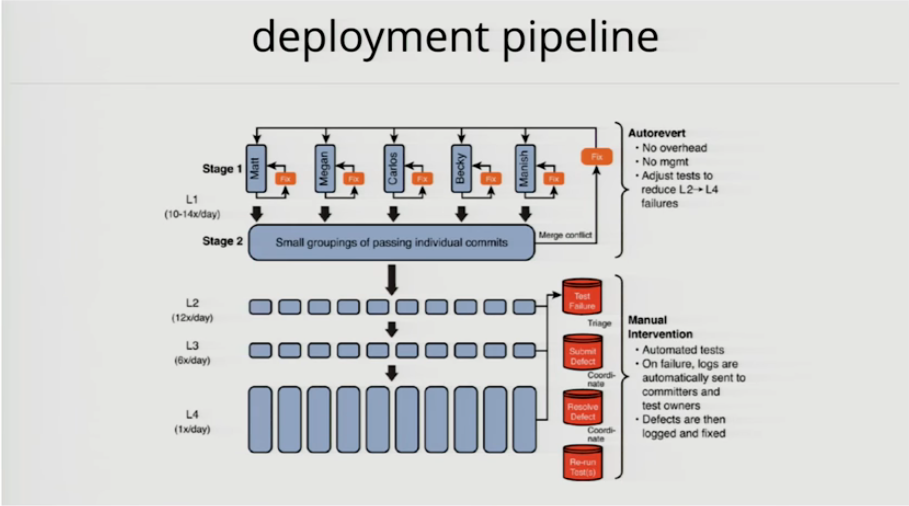

They started with Continuous Integration. But the build was breaking all the time.

In order to make it (so the build was not breaking all the time) they ended up after two years of work and process improvement with this system.

Before the Continuous Delivery book came out. They independently invented Continuous Delivery.

400 engineers working on a 10 million line codebase

-

stage 1: every engineer have their own git repo where they push to

when they push a change, the build runs two hours of automated tests

if it passes, it gets promoted to stage 2

-

stage 2: is always running, it picks up all the changes that passed stage 1 and does a merge, runs two hours of automated tests

if it fails, it sends an email: here is the merge conflict, or here is the stack trace of a failing test; engineers can reproduce that and fix that on their developer workstation

if it passes, code get pushed into trunk

this forces engineers to work in small batches, because you are much more likely to get your changes into trunk when you submit an hours worth of code then if you submit three days worth of code

if you submit three days worth of code, merge conflicts will be a nightmare to resolve

-

level 2: two hours of automated test run that works on simulators

-

level 3: two hours of automated tests (different tests) that work on emulators (actual physical logic boards)

-

level 4: complete regression suite of 30.000 hours of automated tests that run over night

=> developers get feedback within 24 hours

400 engineers able to get 100 changes into trunk each day; about 100.000 lines of code change each day; getting 10-15 good builds each day out of trunk

=> completely get rid of the manual regression phase

it also changes the economics of the software delivery process

Two goals for the re-architecting:

- getting off the critical path

- aiming for a 10X productivity improvement, where they measured productivity in percentage spent on innovation

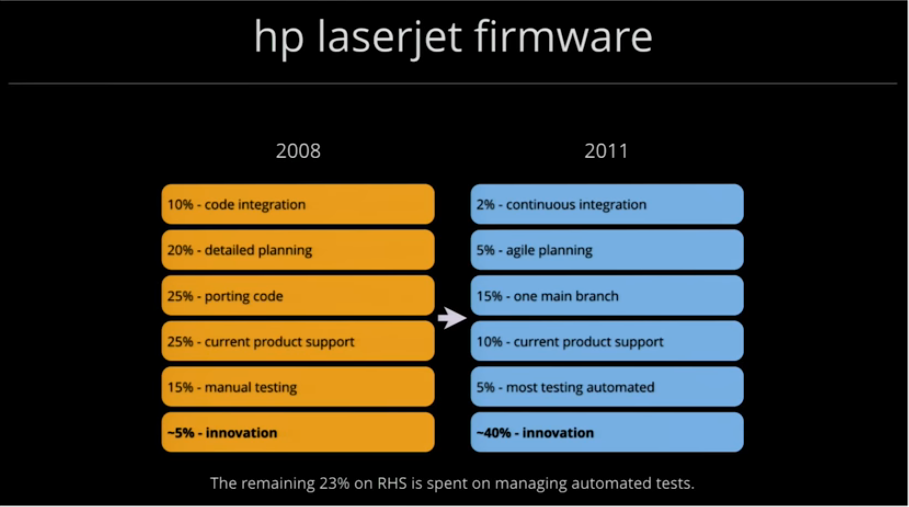

2011:

- 2% continuous integration:

- 5% agile planning: got rid of detailed planning

- 15% one main branch: got rid of porting code, not maintaining branches anymore

- 10% current product support: down from 25% => quality improvement

- 5% most testing automated

- -40% innovation: coming from 5%

=> there is a new activity: 23% of engineering activity building and maintaining the automated tests

the economics: 2008 to 2011

- overall development costs reduced by 40%

- programs under development increased by 140%

- development costs per program down 78%

- resources now driving innovation increased by 8X

Book: A Practical Approach to Large-Scale Agile Development, Gruver, Young, Fulghum

=> Costs go down, Quality goes up, Time to market goes down and we are not deploying 10 times a day, we are deploying firmware

Continuous Delivery is not just about making releases boring. Though that was our goal in the beginning.

The reason it is popular it is because it has all those nice side effects on the software development process and the economics of that process. Continuous Delivery makes it cheaper, faster and higher quality.

Part the third: "too much legacy"

Example: Suncorp

Australia's biggest insurance company

at one point they had 18 different mainframe platforms through acquisitions; they wanted to consolidate that, but in order to do that they had to know they were not breaking stuff

=> build automated test suite to run against those mainframe systems

The green screens are remarkably durable and remarkably quick. They are an incredibly good test end-point.

Testing them is very fast.

We used Concordion.

which substantially reduced the time for making changes and increased the confidence to make releases

However, architecture is important!

Based on our research (4 years of State of DevOps report): Architecture is the most important factor that predicts your ability to do Continuous Delivery.

When people say architecture for Continuous Delivery their minds go: micro services, Kubernetes, Docker. These are great tools, but that is not the critical factor. You can do Continuous Delivery on mainframe.

What we found as critical factors is whether teams can answer these questions:

Can my team …

- … make large scale changes to the design of its system without the permission of somebody outside the team or depending on other teams?

- … complete its work without needing fine-grained communication and coordination with people outside the team?

- … deploy and release its product or service on demand, independently of other services the product or service depends upon?

in other words: do I need to do big orchestrated deployments because everything has to go out in lock step because everything is coupled and releasing is a nightmare or can I push out my service independently without breaking everything else.

- … do most of its testing on demand, without requiring an integrated test environment?

can developers run tests on their workstations and get a high level of confidence that their service is releasable

- … perform deployments during normal business hours with negligible downtime?

– source: State of DevOps Report 2017

Being able to answer yes to these questions is really, really important.

You can do that with mainframes.

You can rebuild your system entirely with Kubernetes and micro services and not be able to answer these questions with yes.

Kubernetes, Docker, micro services, these are great things but you have to do it right. Otherwise there is no point and you have wasted a ton of money. It is the outcome that these tools enable, not implementing these tools that is important.

Don't do big bang rewrite, incrementally change the architecture using the Strangler Fig pattern. That is what Amazon did.

Part the fourth: "our people are too stupid"

Example: Netflix

Adrian Cockcroft, Cloud Architect at Netflix

He went visit other companies

CIO: Where do you get your amazing people at Netflix. Adrian: I get them from you.

His point was not that he was hiring the brilliant people.

His point was that Netflix had built an organisation, a management structure and leadership that enabled people to do their best and create outcomes effectively.

The system is important!

If you hire good people into a bad system, you break the people.

A bad system will beat a good person every time

– Deming

People don't create outcomes. Teams create outcomes. What enables teams is good management and good leadership.

Example: Nummi

My favourite story about organisational change is Nummi.

joint venture between General Motors and Toyota

in 1980 this auto manufacturing plant in California was the worst performing plant in the whole GM North America

the workers were so angry, so dissatisfied, they sabotaged the cars, take drugs, drink, gamble at work, 20% absentee

GM shut the factory and fired everyone

at the same time the joint venture between Toyota and GM happened

the union workers convinced Toyota to hire the same people to work at their new joint venture in Fremont

they sent those people to Nagoya, Japan to work on the Toyota production line and learn the Toyota production system

within a few months, Fremont produced the highest quality cars of any GM factory in North America

It wasn't the people the problem, it was the management!

What happened in the GM factory: QA driven quality process

What happened in the Toyota factory: build quality in, continuously improve the process, andon cord to stop the production line when it is broken

Building Quality In and giving the people doing the work the tools and the ability to build quality in turns out to be what is important.

"Our people are too stupid" turns out that is true, but it is not the people you are thinking of

Resources:

- This American Life on Nummi

- MIT Sloan Management Review: How to change a culture: a lessons from Nummi

What my Nummi experience taught me that was so powerful was that the way to change culture is not to first change how people think, but instead to start by changing how people behave – what they do …

– John Shook

GM totally failed in trying to reproduce Nummi in the other GM North America factories. It took them 20 years to take those lessons and spread them to the rest of North America. By which time GM was gone bust.

The term Lean comes from all those people in that Nummi factory who then went write papers and books and gave talks. They invented the term Lean. That's where it comes from.

(I thought the term Lean was introduced by the book The Machine that Changed the World, Womack, Jones, Roos)

People visit the Nummi plant and tried to copy the system, but it did not work, because managers were still rewarded for the number of cars they produced whether they were working or not.

Same problem with Software Methodologies.

A methodology is a bunch of stuff we do in an organisation then we copy it and do the same stuff and we think it will achieve the same results

This is misguided: taking things that worked in one complex system with a particular set of goals and copying it, does not guarantee you the same results partly because it is a different system and also partly because you hopefully have different goals.

You got to work out for yourself! and the failures you will encounter while working out for yourself are important!

Certainly the thieves may be able to follow the design plans and produce a loom. But we are modifying and improving our looms every day. So by the time the thieves have produced a loom from the plans they stole, we will have already advanced well beyond that point.

And because they do not have the expertise gained from the failures it took to produce the original, they will waste a great deal more time than us as they move to improve their loom. We need not be concerned about what happened. We need only continue as always, making our improvements.

– Kiichiro Toyota, quoted in Toyota Kata, p40, Mike Rother

That is how you implement Continuous Delivery. That is how you get better at what you do. Don't copy what other people did. It is useful inspiration, but it won't create a culture of improvement. You have to do it yourself and management have to focus on helping you do that.

The journey

How do you get started?

-

agree and communicate on measurable business goals

people say to me: "Oh we are going to do Continuous Delivery or DevOps." and I say: "Why?"

What is the measurable business goal you want to achieve by doing that?

I should be able to go to anyone in the organisation and ask them why they do what they are doing. They should be able to tell the measurable organisational business goal they are working towards by doing that work.

One of the most important jobs of leadership: agree on communicating those goals.

-

give teams support, time and resources to experiment to work out on how to get better

because you can't copy what others do, you have to work it out yourself

-

talk to other teams

especially the people you are afraid of talking to

one of my most important CD hacks was: go and find the team that pisses you the most of and go and buy them lunch, ask them why they are mad and spend an hour listening to them and then find some way to help them

-

achieve quick wins and share learning

source: 6 Steps to Survive a DevOps Transformation

It it's a good idea, go ahead and do it. It is much easier to apologise than it is to get permission.

– Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, USN, 1906-1992

Source: https://thinkinglabs.io/notes/2021/12/11/agiletd-continuous-delivery-sounds-but-it-wont-work-here-jez-humble.html

0 Response to "Continuous Delivery Sounds Great but Will It Work Here"

Post a Comment